When I first heard that levels were being abolished the implications escaped my initial blasé attitude. ‘We’ll just end up doing the same thing’, I mused. How wrong I was.

Less than a month ago I encountered the resource my school had invested in as a foundation for our own venture into a world without levels. I went home with a migraine and verging on tears. I’d spent hours trying to interpret a behemoth of a spreadsheet that included every single function a teacher could possibly need without actually being functional.

Since then, colleagues responsible for spearheading this have clarified that it’s just a starting point and definitely needs tweaking. They’re teachers like me, of course they have, no one would believe that in its existing form it would serve the purpose required.

However, my initial terror served a valuable purpose; it inspired me to not be a ‘nimby’ style teacher, moaning about everything without actually doing any research or work into a viable alternative. So that’s exactly what I did. I spent hours trawling the net looking at EduBlogs and resources shared by teachers like myself going through the same process.

It didn’t take long to realise that most English faculties across the country had decided to make the most of the fact that our new GCSE specifications and assessment objectives are available and use those to plan backwards.

Planning backwards is not a new term, nor is it revolutionary. By looking at where we want students to be when they’re in Year 11, we simply plot a course back to Year 7 to see what steps they need to be making along the way.

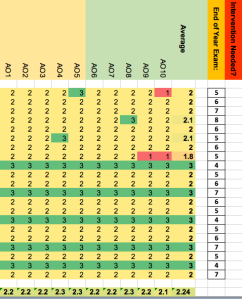

I therefore, like many others, decided that three sets of Assessment Objectives, (AOs), for Years 7, 8 & 9 would be a good way of ensuring a natural progression from Year 7 to 11.

Didau states that, ‘consistent progress’ is more desirable than ‘rapid progress’ – he and I agree on this. I wasn’t going to design a million criteria to track the minute nuances of understanding of students. I simply wanted 10 basic skills, (or AOs), that students work towards year after year, with each year’s objectives being a natural step up from the year before.

Tracking progress here is simple – they are either achieving the objective or they’re not, this can be recorded using a basic RAG rating. In Term 1 therefore it’s unlikely you will see lots of amber and green, but you’d better hope that’s changed by July or you’re doing something wrong!

Whether we like it or not though, progression needs to be evidenced, (and to an extent quantified), in order to prove that we’re doing right by our students, and to make future predictions on outcomes.

The system we’d been given as an example used steps of progress, (1 to 9 naturally), for all of the criteria they had created off the back of the new NC. You’d therefore be grading students against at least 80 (!) criteria throughout the course of a year. This would be based on class assessments and teacher’s judgements.

My problem with this is how shallow your judgements would be if you need to make so many: in the course of a year would you have any opportunities to revisit skills if there are so many?!

This is why we scrapped this concept and replaced the tiered skills with simple objectives you’ve either met or you haven’t. But how do you know what progress a student is making in relation to their prior attainment and that of their peers though?

I suggested, with a heavy heart, that end of year tests would eradicate this problem. They would be based upon the AOs, use GCSE-style terminology, award a grade from 1 to 9, and be a level playing field across the year group. If these were made more challenging each year, one could also quite accurately predict a student’s success at GCSE if you used a flat-line progression map. E.g. A grade 5 in Years 7, 8 and 9 would show progress, (as a 5 would be more difficult to get each year) and would probably indicate that is the grade they will achieve at GCSE.

So much for a life without levels eh?

Now, this might seem like we’re making a rod for our own backs and that we’ve become the thing we used to detest, but bear with me.

What are the benefits?

- Levels were never designed to be a label stamped on children, students don’t need to be told what level they are all the time, and we shouldn’t feel we need to tell them – a new system where students are not told ‘grades’ or ‘levels’ ensures they focus on the important thing:

What am I good at? What do I need to improve?

- With a curriculum shift we can develop higher expectations sooner. I’ve made the Year 9 objectives, Year 8 ones and so on and so forth. We can improve GCSE results exponentially if students are becoming GCSE ‘ready’ by Year 10, with KS4 being an opportunity to learn advanced content.

- Staff will use a system effectively and with discipline if they see the advantages laid out before them.

- Using a spreadsheet to track students’ ability to achieve the AOs we can spot trends in teaching and learning:

As you can see, with students’ individual records going horizontally you can see their overall progress, as well as AOs vertically – allowing you to develop CPD opportunities to help your team with gaps in their knowledge.

However, I have not been naive, there are certain obstacles to overcome, namely:

- Our system needs to provide the same level of feedback and detail as all other departments; we cannot be perceived as the ‘weak link’.

- Current SoWs will need to be tailored to ensure that the AOs are being covered in specific lessons/units, there needs to be enough coverage across the curriculum.

- Time-Effective: Our system needs to be manageable. Teachers need to become as au fait with the AOs as possible to address gaps in understanding quickly and effectively. This is impossible with an overly-complex tracking system.

I am not arrogant enough to presume this system is perfect, nor am I adverse to suggestions, so please comment if you have any thoughts! However, I went from being a teacher who was struggling to interpret a spreadsheet to one whom was making his own from scratch. In retrospect this is exactly what SLT wanted – they weren’t giving us the answers, they were helping frame the questions.

I apologise if this article has seemed overly detailed, it’s very difficult to convey via a blog, but I can summarise everything into 5 top tips:

1. Don’t just stick to what you’ve always done. GCSEs are changing whether you like or not, you’re going to need to adapt.

2. There are lots of models and frameworks available out there, both free and at a cost. But don’t just think money is the answer, time and many conversations with your department are the only solution – put it this way, the person who made that spreadsheet you downloaded has never met one of your students, so do you trust them with their future?

3. Keep it simple, and time effective. It doesn’t matter where you work, you will have colleagues who are diligent and those who are less so; by making the system easy to use, everyone can use it, and furthermore, get good at using it – which is far more important.

4. Decide what fits in with the ethos of your school. I am lucky enough to work in quite a flexible institution and I know that all other departments will be creating a system not too dissimilar to mine. If yours does not fit the mould though, how will students and parents make sense of it?

5. Know one thing: This matters. Think of all those times where you have been asked to work on an initiative or idea you know will disappear after a month or so, it was time wasted and well all know that. This isn’t one of those times – the work you do now will pay off dividends in the future. Don’t settle for second best.

That’s it for now, I hope this has allowed you gain an insight into how your department can cope in a world without levels. Please comment if you would like to share your own experiences.